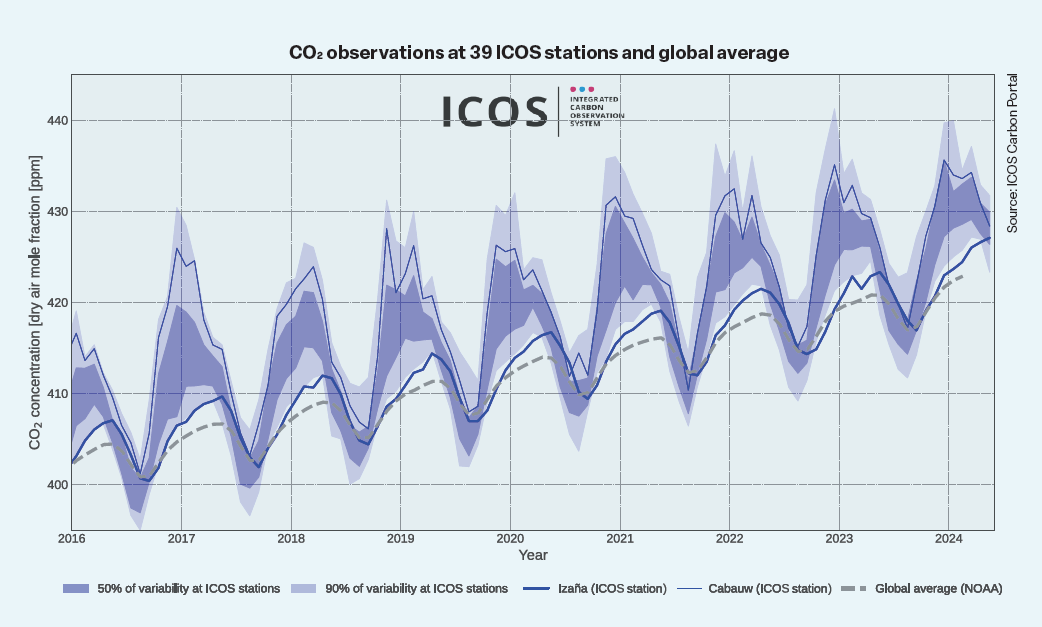

Almost weekly, we hear about floods, droughts, heat waves and the related loss and damage including public health emergencies. Climate change is progressing and the time to act is now. The truth is not in glossy speeches made at international conferences, like COP28, the truth is in the atmosphere. Global warming is caused by excessive concentrations of greenhouse gases and the inconvenient truth is that these continue to rise unabated (see figure below).

Almost a decade after the Paris Agreement, we still see increasing fossil fuel emissions every year. While the window for action is closing, the world is still waiting for a real turnaround in fossil fuel emissions and the decarbonisation of economies.

Over the last few decades, the scientific knowledge about greenhouse gases and our capacity to observe concentrations and fluxes has grown significantly. Scientists now have a large toolbox to support societies in their efforts to curb fossil fuel emissions. In addition, researchers can help identify the best ways to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

"Science supports societies in being efficient in their climate actions."

In this edition of FLUXES, we want to open this toolbox and explore how science-based Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) systems are part of the solution. This is not trivial – there are many different perspectives on what MRV systems are:

Monitoring (or measurement) refers to data and information regarding emissions. Depending on the MRV system in question, this could be measurements of greenhouse gases or emission estimates. The UNFCCC system uses emission inventories based on statistical data on activities and related emission factors, while scientific approaches use observations of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, for example.

Reporting is the act of compiling this information into inventories and disseminating them (e.g. to the UNFCCC). This ensures that the monitored information can be accessed by a variety of users. Scientific reporting may happen via the IPCC or independently by NGOs, such as the Global Carbon Project.

Verification is, within the UNFCCC process, the act of another party independently verifying the reported information to ensure accuracy. Scientifically, the term also includes the reconciliation of reported inventories and greenhouse gas observations, meaning that an independent parameter (e.g. greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere) ‘verifies’ the reported inventory of a country or region which helps improve its accuracy.

All of this means that MRV is a critical tool for tracking climate action and empowering countries to improve their progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In this volume of FLUXES, we are exploring how research, systematic observations and ICOS scientific community can be of support in employing MRV systems.

The dark purple area in the graph shows typical CO2 concentrations for Europe from about half of the ICOS stations each month.

The lighter purple areas include the remaining stations, of which 25% are above the dark purple range, and 25% are below.

Two of the measurement stations, Izaña and Cabauw, are located in environments representing two extremes and, therefore, showing bigger variations in emission patterns. The mountain station Izaña in Tenerife, Canary Islands, is representative of so-called background conditions, far from human-induced emissions. In contrast, the Cabauw station is located in between the triangle of the major cities of Rotterdam, Utrecht and Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations are inexorably increasing

Latest ICOS data displays an annual growth rate of 2.7 ppm CO2 in the atmosphere during the year 2023. Most of this increase is due to fossil fuel emissions which were still not reduced.

The ICOS network of systematic observations and near-real-time monitoring of greenhouse gases gives information on fossil fuel emissions. It also reveals how the natural carbon cycle responds to extremes and explains the slight increase in 2023 compared to previous years. The climate phenomenon El Niño influenced the natural carbon fluxes. Consequently, more of the CO2 from fossil fuel emissions remained in the atmosphere and the atmospheric growth rate increased.