Photo by Jarvoslav Monchak

A global effort is under way to provide near real-time data on greenhouse gas concentrations covering all continents. Launching in 2028, the Global Greenhouse Gas Watch (G3W) initiative brings together a global network of satellite operators, surface-based observation systems and modelling expertise to gather the best existing knowledge and technology. In Europe, Copernicus and ICOS are providing the blueprints for the monitoring system.

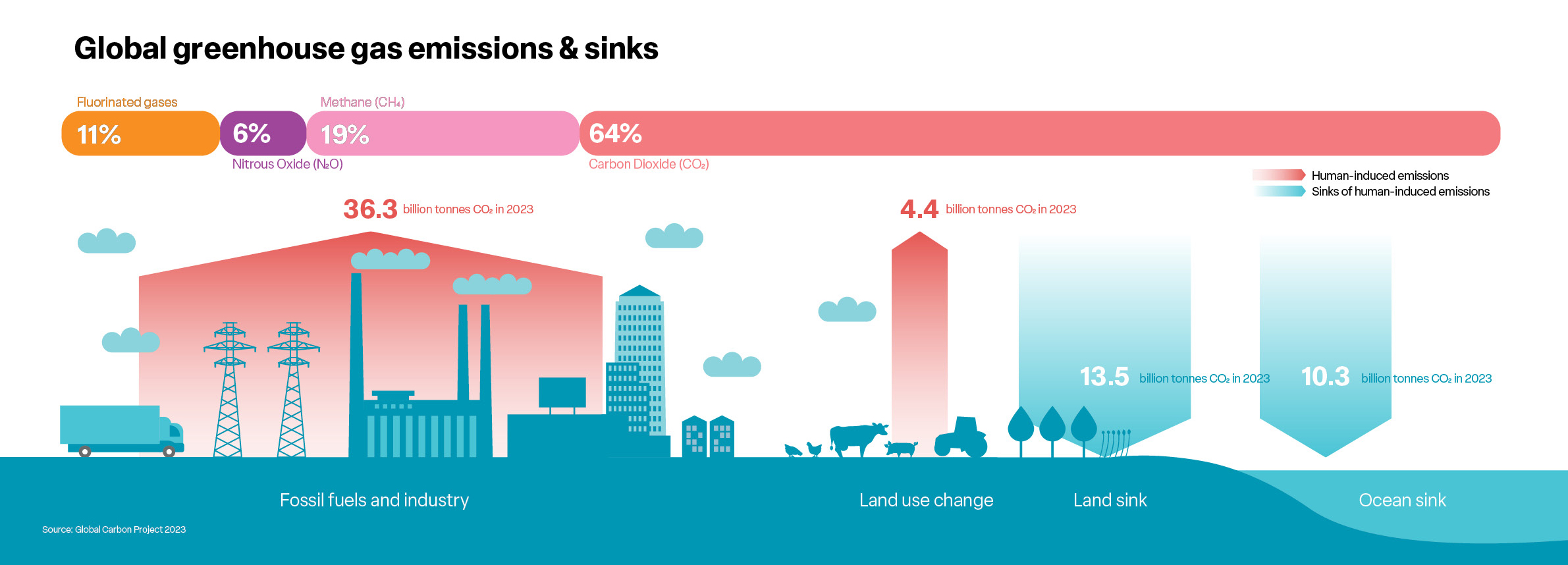

Despite claims of emission reduction efforts, global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, with 40 billion tons of CO2 still emitted every year. While the world’s land surface absorbs roughly 10 billion tons and the ocean another 10 billion tons, half of the global emissions are left in the atmosphere each year.

“Atmospheric concentrations of the main greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide are all increasing, which is connected to a carbon economy and the dominant use of fossil fuels,” says Dr Gianpaolo Balsamo, Director at the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), leading the Global Greenhouse Gas initiative (G3W).

The G3W is a complex observational network covering almost all domains: land, ocean, atmosphere and cryosphere (ice caps, glaciers and areas of snow and permafrost). It consists of surface-based and space-based observations and requires a large-scale collaboration between international organisations, government agencies, research institutions, the private sector, and a variety of initiatives.

In Europe, the G3W will mostly build on the existing technology and knowledge from Copernicus and the Integrated Carbon Observation System (ICOS). On a global scale, the G3W will integrate systems from all the continents under one global umbrella.

“It is a very collective work. We need to make the different communities come together - the modelling, observations, ocean, terrestrial and air quality sectors, but also geographically - the North Americans, Europeans, the Chinese, Japanese, etc. We need to work together to develop a common plan,” says Dr Vincent-Henri Peuch, Director for Engagement with the EU and Head of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF). He has been leading the group developing the G3W implementation plan.

Real-time data for informed decisions

The G3W system, due to be partly up and running in 2027, is designed to track greenhouse gases across the globe, particularly CO2. The aim is to compile monthly data on greenhouse gas observations at a 100 km x 100 km grid on a global scale. The ultimate goal is to reach a 1 km x 1 km grid within the next decade. The G3W data will support the greenhouse gas inventories with dynamic, timely and geographically detailed data, using observations, data management and modelling.

Unlike inventories, which are produced annually and focus on national or sub-national totals, the G3W network will provide a more dynamic, faster response with monthly results. This offers valuable insights into the Earth system's responses to occurring changes.

“This way, we get a tool to inform and guide climate action as well as evaluate the efficacy of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs),” says Balsamo.

The World Meteorological Organisation is relying on a range of collaborations with existing observational networks to set up the G3W system and the 193 WMO member countries need to stand behind it. The system comes with a hefty price tag: The total global cost estimate for the project is $1 billion. The aim is to save costs using already existing infrastructures and capabilities in the member countries to avoid duplication and enable a rapid path from research to operation.

“To be clear, the G3W is not just one system – we are talking about three, four, five systems spread across the world. The figures coming from Europe, China, USA or Japan will be reasonably compatible. If all the systems are converging, i.e. saying that emissions are higher or lower than what is estimated, it will be a very good incentive to look into detail," says Peuch.

The implementation plan will be presented to WMO member countries in June 2024 and then the concrete work can start. According to Peuch, one of the biggest obstacles is presenting the products for what they are.

“It would be a big danger to appear as the greenhouse gas police and basically present figures that would make the UNFCCC parties very uncomfortable,” says Peuch.

“The UNFCCC parties mostly use inventories for statistics right now – the G3W products will be as good or as bad as forecasts – they are a piece of information and evidence that we can bring to the country as additional information. It is not a ‘big brother watching you’ type of approach, instead it is supporting the countries to see whether the measures that are taken are effective,” he adds.

The G3W system will help improve the quantification of both natural and human induced greenhouse gas sources and sinks.

“It will allow us to see how much greenhouse gases we emit, how much CO2 enters and exits the atmosphere. This will significantly improve the accounting on who is doing what. We basically need to solidify the scientific basis for decision making. Otherwise, the necessary decisions will not be made,” says Dr Lars Peter Riishojgaard, former WMO Director and one of the G3W lead architects.

Overcoming challenges monitoring remote areas

The preparations for setting up the G3W network are already progressing at full speed, according to Senior Scientific Officer Dr Oksana Tarasova at WMO, one of the initiators of the project.

“We should have pre-operational data and a first mock-up of the system in 2027. The second Global Stocktake will wrap up in 2028 and the G3W will feed into that,” she says.

“Then, the initial operational phase starts, where we identify and mobilise resources to build the most critical elements to move to full implementation. By 2032, the enhanced operational phase of the G3W will support the Paris Agreement implementation by assessing the impact of policymaking,” she explains.

However, implementing a global initiative of this scale poses several challenges. The plan is to start with a comprehensive assessment of available observations to make use of the already existing infrastructure in the different countries. Satellite, sensor technology and observational coverage are already at advanced stages in the United States and in Europe, and emerging in China and Japan. However, there are areas of the globe that need to be covered where the technology is still not in place and surface-level observation is required.

“We do not have enough surface-based observations. The tropics are incredibly important because most of the terrestrial carbon is stored there, and so we need to monitor them much better than we are doing today,” says Riishojgaard.

In addition to the tropics, there is a lack of comprehensive surface-based observations, particularly in the boreal forests, permafrost areas, and the global ocean areas.

“75% of the planet is ocean. We do have satellites that are global in nature, but the satellite observations are not sensitive enough to measure the differences in atmospheric concentrations over the ocean. Therefore, we have a strong need to observe the ocean concentrations also from surface-based platforms, for example from ships. So we need to be pretty creative,” says Tarasova.

To help tackle this, the G3W network is aiming to set up strategic partnerships with shipping companies, airlines, and cell tower operators to enhance observational capabilities, particularly in remote areas. Moreover, it is important to transition from research-based observations to an operational system with 24/7 capabilities, says Tarasova.

“On a global scale, there is a lack of investment in atmospheric observations and modelling. Unlike research projects dependent on fixed-term funding, we need to aim for a routine, sustained data production, ensuring continuous output independent of fluctuating research funds,” she explains.

“At a political level, there should be a push for additional use of direct atmospheric data in support of climate policy, which is not the case. In the political processes we need to get much better representation of what happens in the real world – and the answer is not in the carbon credits,” she adds.

Empowering nations to boost observation

G3W aims to give a comprehensive picture of the state of the atmosphere, land, and oceans – but that requires all nations to have the capacity to contribute to real-time measurements and data collection. In Europe, there is already good observational coverage.

“ICOS is the key player for surface-based observations in Europe. It has provided the leadership coordination on many aspects and is a major asset. The other important player in Europe is Copernicus. Together, we are bringing together a big number of very important academic institutions,” says Peuch.

However, a 2023 survey of the 193 WMO member countries, showed that up to 63% do not have a greenhouse gas monitoring plan in place.

“That is a majority of countries, which means that the G3W products would really be needed. The G3W will allow all the countries of the world to have the figures and to use them to make plans, update them and report their emissions using tools that are at the same level as the most advanced countries in the world,” says Peuch.

The climate crisis and the lack of equal possibilities to contribute need to be tackled at the same time, according to Balsamo.

“In practical terms, we have to bring all countries to a sufficient level of greenhouse gas monitoring through a capacity building effort. We need to invest substantially to permit every country to engage in surface-based observations, quality control and assessment, verification, and reporting. Empowering the nations on the monitoring is a key aspect. But we must be mindful of being inclusive. That's the number one priority,” he says.

On the other hand, political or economic tensions can have a big influence on observational networks. In 2021, the Russian government stopped its greenhouse gas measurement programme. The country has the most extensive area of boreal forests in the world, an immense carbon reservoir.

“They also have the largest area of permafrost, which is sort of a ticking time bomb because it's slowly melting, and it will outgas a lot of methane. We don't know exactly how quickly or how much,” says Riishojgaard.

Diversity of economic and political interests

Another significant hurdle in the implementation of G3W is the diversity of economic and political interests, especially in countries heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

"As a minister once said in one of our meetings - the problem is that we don't know how to do what we need to do and get re-elected," Riishojgaard says.

According to Tarasova, there could be a way to bring monetary resources to countries that may not be able to fund observational networks themselves.

“There could be a mechanism that allows those countries that cannot meet the minimum technical or financial requirements for measurements to get funds from the G3W system. The money could come from development funds and be results-based – as long as you deliver data, you get the funding," Tarasova says.

Managing the reduction of greenhouse gases according to the Paris Agreement is a binding pact, but the world still needs concrete means to follow up on its actions.

“The nations need a reliable greenhouse gas monitoring system that is based on science and observational evidence, and that can serve the 198 UNFCCC parties, keeping the goals of the Paris Agreement within reach. The solution is the Global Greenhouse Gas Watch, which is solid, valuable and necessary to mitigate the risks that climate change poses to society,” Balsamo concludes.